In this issue, THINK’s Chief Editor spoke with filmmaker and anthropologist Ian McGonigle about his award-winning documentary Technologies for the Soul. The film examines how technologies —from smartphones and AI-powered chatbots to robot monks and digital rituals — are transforming spiritual life. Filmed in Singapore across multiple faith communities, the documentary investigates how traditional beliefs are adapting in response to digital disruption, and whether machines can ever mediate, perform, or even embody the sacred.

PROF IAN MCGONIGLE

Prof Ian McGonigle is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Maynooth University. Previously, he was a Nanyang Assistant Professor at Nanyang Technological University, where he founded and directed a Science, Technology, and Society research laboratory. He earned a PhD in Middle Eastern Studies and Anthropology from Harvard University, as well as a PhD in Molecular Neurobiology from the University of Cambridge. His work in the anthropological study of science examines the role of science and technology in identity formation and nation-building. His book, Genomic Citizenship (MIT Press 2021), explores the relationship between science and identity in the contemporary Middle East. He also co-edited with Rachel Feldman, Settler-Indigeneity in the West Bank (McGill-Queen’s University Press). In recent years, he has produced two multi-award-winning documentary films about science, identity, and religion. Ian is currently interested in the relationship between artificial intelligence and religious practices.

What inspired you to create Technologies of the Soul, and how did Singapore’s unique religious landscape influence your approach?

The inspiration came during the pandemic, when our lives became increasingly virtual. I noticed an intense and pronounced shift in how we interacted with technology—with more meetings going online and with many more hours per day in front of screens—and I became curious about how this affected spiritual life and traditional forms of community gathering and interaction. At the same time, I was realising that Singapore is perhaps the most religiously diverse place on the planet, with ten officially recognised religions. It is also a technological world leader, the ‘Smart Nation,’ so it’s a place where deep tradition and rapid change coexist, making it an ideal site for exploring how religious communities respond to technological change.

In the documentary, religious leaders you interviewed expressed differing views on technology and social media, ranging from distractions to neutral tools to something that facilitates spiritual connections. What tensions or contradictions did you observe in how religious communities navigate the promises and risks of social media and mobile technologies?

There was certainly a wide spectrum of views. Some interviewees saw technology as a neutral tool—the example used to illustrate this point was that a knife could be used for violence or for preparing food for a guest—while others were more cautious, concerned about doomscrolling, digital distraction, and pushing our bodies out of their natural rhythms and harmony with nature. There was no clear consensus across the ten religions, nor was there a sense of alarm or outright rejection of technology. If we focus on religious education, then we can clearly recognise the power of digital media to transmit information more efficiently, but if we think of the more predatory and pernicious forms of social media, we can see how our attributes of envy, greed, and status seeking may be nourished. My view is that both aspects can coexist and that we can be ambivalent about digital technologies since they pull us in both directions. Different religious groups will ultimately develop in their teachings good guidance on how to extend the pursuit of an ethical life into online spaces.

Balancing religious harmony and digital challenges

Positioned as a Smart Nation with ten official religions, Singapore faces ongoing challenges in preserving interfaith harmony amid rising digital connectivity. The Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (MRHA), first enacted in 1990, has expanded over time to address online discourse and foreign influence, reflecting a broader shift toward tighter regulatory oversight in safeguarding social cohesion..

Unsplash / Cole Keister

While conventional face-to-face leadership and pastoral life are as important as ever for individuals to experience community support, online spaces add another dimension to contemporary religious life, particularly educationally.

In the documentary, you show how digital platforms help extend spiritual practice beyond traditional spaces. From your perspective, do you see this expansion as transforming the very nature of religious authority or leadership? Who is shaping spiritual narratives now in these online environments?

Absolutely. I believe that when the metaverse was initially launched, one of the most popular hangouts was the digital Chabad house, which is a meeting place for Orthodox Jews. So, there is no doubt that the online world has become a legitimate mode of assembly for ultra-traditional faith groups. I am not sure if religious authority itself is being challenged in a unipolar way. It seems to me that many charismatic religious leaders are now extending their teachings online, on YouTube or TikTok, for example, and developing larger followings. So, if in the past we lived in scattered, unconnected communities, each led by its own community leader, it may be that we are entering a more competitive era where the more successful preachers can command a massive following online. Just think how many people a traditional sermon might reach in its congregation, perhaps a few hundred. Now, a popular preacher can reach millions of viewers within minutes, so the positive potential for spreading good messages is immense.

While conventional face-to-face leadership and pastoral life are as important as ever for individuals to experience community support, online spaces add another dimension to contemporary religious life, particularly educationally. This democratisation can be empowering, no doubt, but it also raises questions about whether there is a danger of loss of community or solidarity at the local level. It’s perhaps a shift from a hierarchical form of organisation to more globally networked and extended forms of spiritual engagement.

A synagogue in the cloud

Built by Chabad-Lubavitch on the Decentraland metaverse platform, the MANA Jewish Center blends immersive technology with traditional outreach. Modeled after the movement’s Brooklyn headquarters, the virtual synagogue hosts Torah study, events, and social gatherings — extending Jewish life into digital realms while remaining rooted in real-world practice.

Source: MANA Jewish Center

With religious leaders now competing for attention in the online world, how do you think this shift affects the depth and quality of spiritual guidance? Do online religious activities dilute or enhance spiritual authority?

We can clearly see the trend towards social mediation of religious content as democratising and creating avenues for the most popular or persuasive voices to command a massive following, bypassing traditional gatekeepers and institutional authorities. This includes preachers on YouTube or TikTok who are commanding millions of followers. On the one hand, this ought to allow the brightest and best to maximise their positive influence. On the other hand, we also know that negativity and extremism can also flourish online—for example, on Twitter, or X now—and conflict and bigotry can command much attention. There is an open question about how to regulate and control what kinds of messages are permitted and which are clearly harmful to social harmony and community solidarity. That is to say, how do we calibrate and get the right balance between protecting individual liberties and protecting social cohesion? So there is a two-way potential for massive positive influence as well as catastrophic social harm. This also raises a huge question about defining the borders of free expression and criticism online and how we can balance this freedom in relation to the integrity of the community, especially in diverse societies like Singapore.

AI Jesus confessional

At St Peter’s Chapel, the oldest church in Lucerne, Switzerland, a computer now hears confessions in place of a priest. Dubbed Deus in Machina (“God from the Machine”), the AI-generated Jesus, trained on biblical texts, responds to visitors in over 100 languages. Visitors are advised not to disclose personal information — an ironic note in a booth once meant for the soul’s most intimate revelations, now becoming a symbol of faith mediated by code.

Source: The Catholic Church of the City of Lucerne

Throughout history, every major communication breakthrough—from the printing press to radio and television—has transformed religious life, often prompting both institutional and grassroots adaptations. In your view, how does today’s digital transformation compare to those past shifts, and do current responses within religious communities feel more driven from the top down or bottom up?

According to the Abrahamic traditions, God spoke directly to Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Mohammed, imparting divine instructions on how to live an ethical life and establish moral societies. These principles are codified in the Torah, New Testament, Qur’an, and in clerical commentaries on these sacred texts over hundreds and thousands of years. Revolutions in textual transmission practices, especially the invention of the printing press, and the translation of these texts from their Semitic originals in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic to local vernaculars have precipitated schism and social reform, including the European reformation of Christianity, the reform movement in Judaism, and Islamic modernism. In a dialectical move to negate these movements, the Abrahamic faiths have also seen anti-modern retrograde moves to return to orthodoxy, with Christian fundamentalism, Hasidic Judaism, and Salafi Islam.

The point that technological rupture can engender theological revolution and societal upheaval is well taken. Today, we are at a profound junction in the history of religious life, as digital media has made available massive volumes of esoteric and sacred texts that for millennia were the privilege of elite scholars to study and critically engage. Suddenly, the scriptures are available for instant translation and penetrating exposition, accessible to all with an internet connection. Moreover, with the addition of large language models, esoteric texts are now available to engage with through real-time chatbots that can parse, summarise, and critically analyse in ways that surpass all but the most erudite experts.

Faith goes viral at Vatican

The Vatican inaugurated its first Jubilee dedicated to digital missionaries and Catholic influencers on 29 July 2025, gathering over 1,700 Catholic creators from 75 nations in Rome. Recognising social media as a powerful platform for spiritual unity, Pope Leo XIV encouraged them to transcend mere content creation and authentically “go and mend the net”— a clear acknowledgment that the internet has become a vital terrain for evangelisation.

Photo: REUTERS / Remo Casilli

Indeed. The film highlights how access to sacred texts is now widespread and instantaneous. Do you think this democratisation changes the role of religious scholarship? Could it risk oversimplification or misinterpretation?

Fabulous question! This is one of the avenues my research has taken me recently, and we will have to closely follow how the emergent technologies will reconfigure different religious groups over time. For the religions that are intensely text-based and where scholarly competence is highly valued, the impact may be more intense. In religious groups that more proportionately emphasise individual piety and self-discipline, the consequences of information access may be less. The dynamics will also likely be very different in different parts of the world, so this is definitely an empirical question for social science researchers to follow up on.

But yes, I do think there is the potential for misinterpretation, blasphemy, as well as completely novel and deep interpretations of ancient scriptures, which could lead to new faith group formations. After all, the printing press engendered the European reformation of Christianity. We can hardly imagine what AI will do to the world’s religions in the years to come.

Today, we are at a profound junction in the history of religious life, as digital media has made available massive volumes of esoteric and sacred texts that for millennia were the privilege of elite scholars to study and critically engage.

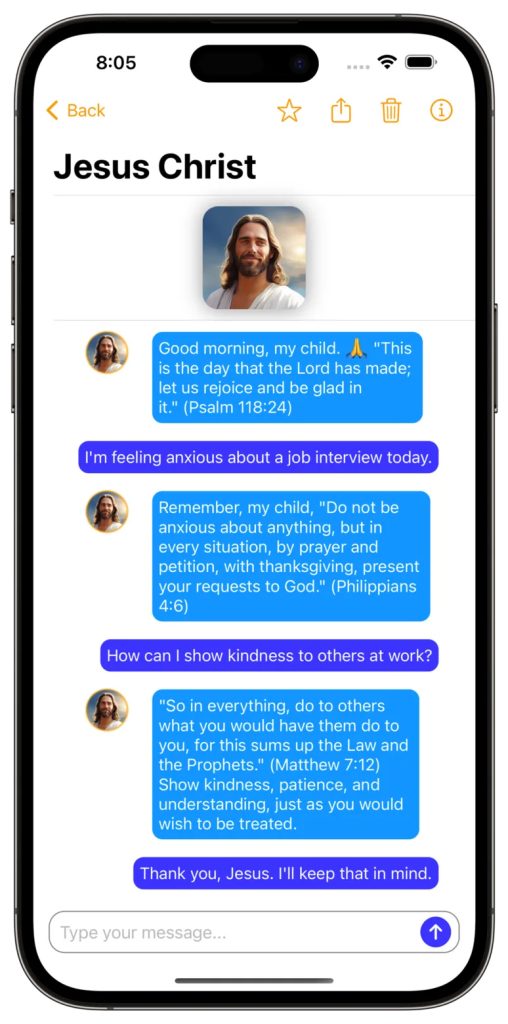

When divinity is just a swipe away

AI apps like Text with Jesus turn the Holy Family, apostles, prophets — and even Satan — into chatbots offering instant spiritual advice on demand. Marketed as tools for connection, they risk flattening rich theological traditions into scripted simulations, blurring the boundaries between faith, entertainment, and algorithmic authority.

Source: Text with Jesus website

Some religious rituals are deeply embodied and sensory, requiring physical presence, space, and community. How are these ideas of ‘sacred time’ and ‘sacred space’ being challenged or reinterpreted in the era of virtual gatherings and online worship?

Virtual worship or prayer services have really blurred the boundaries of sacred time and space. Rituals once tied to physical locations are now accessible from anywhere, even across different time zones. While this increases accessibility and can be more inclusive, it also raises questions about the depth and importance of communal and embodied experience. Take singing in Church, for example. Can a participant have the same sense of group harmony and individual transcendence online? I don’t think so. Many traditions are embracing this flexibility with online participation, and clearly, there are benefits, but there is a cost that may erode the normative expectations of what it means to be a community member. How that balance is calibrated and enforced is another question, but we could start by educating people about the well-being benefits of having a rich community life.

You touched on the risk of losing community and solidarity at the local level. Have you seen any successful models where online and offline religious life complement rather than displace each other?

The pandemic was a remarkable example of how traditional religious life went online in an unprecedented way, and many religious communities conducted their services online and in a hybrid fashion. The legacy of this shift is that some communities have retained a hybrid model, so that those who have difficulty getting to the physical gathering are still included, but this has also challenged the traditional notion of what it means to be in a community, not to mention the loss of the incidental interactions that go along with attending community gatherings.

In terms of the future, it is really hard to predict. When the metaverse was launched a couple of years ago with great hype, many people thought that this was the direction that community life was heading in, but it turned out to be a massive flop. I think we need to think in a more dialectical way about the relationship between online and offline: the more things go online, the more valuable and special it is to be physically present, so I don’t see the relationship as one of displacement but rather one of a dynamic relationship that will change the meanings of online and offline over time. Both can thrive.

Many traditions are embracing this flexibility with online participation, and clearly, there are benefits, but there is a cost that may erode the normative expectations of what it means to be a community member.

The first monk of the machine age

Robot Monk Xian’er, unveiled in 2015 at Beijing’s Longquan Temple, marked a pioneering moment in religious AI. With its cartoonish robes and Buddhist teachings, Xian’er offered scripted wisdom to visitors, blending ancient philosophy with emerging technology. As one of the first spiritual robots, it stands as a historical milestone in today’s growing landscape of AI-powered monk figures.

Photo: Reuters / Kim Kyung-Hoon

I was surprised by the openness of some very traditional movements to the idea that machines could have spiritual significance... It raises the question of whether one might be able to upload their soul to a digital server!

Hinduism and non-human consciousness

Hinduism’s understanding of consciousness is expansive, recognising it as a universal, all-pervading reality (Brahman) present beyond individual beings. This worldview naturally accommodates the possibility of non-human or non-biological consciousness, making Hinduism philosophically receptive to discussions about AI and digital entities possessing forms of awareness or spiritual significance.

Photo: Unsplash / Dmitry Voronov

Have you observed generational differences in how religious practices adapt to digital life? How do younger people of faith navigate between ancient wisdom and constant connectivity?

Generally, we tend to think that the younger generations are more comfortable with digital tools, and there is an idea that Gen Z, the first digital natives, take much of this for granted. Whether this is a fixed characteristic of generations or whether, over time, we will see a reaction against a sense of mediated alienation and thirst for a traditional form of community is not clear. This film didn’t really capture attitudes across age groups or across time, so I think that this is an important topic for further social research. Perhaps an upcoming scholar can do a PhD on the topic! There is plenty to investigate.

Did making this film change your own perspective on the evolving relationship between technology and spirituality, particularly in light of emerging tools like artificial intelligence and virtual influencers? What surprised you most about how traditional or modern faith communities are engaging with these new technologies?

I was surprised by the openness of some very traditional movements to the idea that machines could have spiritual significance, the idea that a robot could pray on behalf of a person, or light ritual candles and perform blessings in lieu of a person. It raises the question of whether one might be able to upload their soul to a digital server! Indeed, scholarly debates rage over whether AI can possess a soul. Some traditions, like Hinduism, are in fact more open to the idea of non-human consciousness, while other religions, particularly those with literalist interpretations of scripture, will resist such notions. This divergence reflects broader theological tensions about the nature of consciousness and divinity, and you can see this in the film.

In terms of what is coming next, AI is already reshaping religious life in profound ways. Over the past five years, large language models like Google’s Gemini, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Copilot, Grok, and others have become widely and freely available.

Subsequently, specialised online AI chatbots have included AI gurus and prophets, like AskBuddha, Rebbe.io, Jesus AI, or Muslim AI. Through these chatbots, users can have a direct dialogue with avatars that are programmed with the sacred scriptures. These new technologies foster novel ways of mediating between individuals, sacred texts, religious leaders, as well as with deities, prophets, angels, and divine emanations. Could it be that a new era of religious life is about to begin? I think this is a very exciting time for religion and technology, and it really challenges our ideas about what makes humans special.

What I learned from the ten religions of Singapore is that traditional practices can comfortably coexist with significant technological change and that what is important is that the moral values of the tradition remain alive and safeguarded online.

Of the self, for the soul

Ancient religious rituals such as prayer, fasting, sabbath-keeping, and confession, can be seen as technologies of the self. These practices cultivate discipline, self-awareness, and ethical formation. Beyond tradition, they shape how individuals govern themselves spiritually and morally, offering structured ways to reflect, regulate desire, and connect beyond the self in a distracted digital age..

Photo: Unsplash / Ashley Batz

In your view, what lessons can spiritual traditions offer to help society manage the challenges of digital overload and the attention economy?

When we browse or scroll mindlessly online, we are engaging in a kind of primitive data-hunting behaviour, constantly filtering for value, and our base desires for personal gain are unavoidably aroused. This couldn’t be further from the kind of peaceful and focused mindset that many ancient spiritual traditions aim to inculcate through sacrifice, prayer, meditation, fasting, etc. I think that this imagined dichotomy motivated my project to seek out how religious groups navigate the challenge of cultivating a healthy relationship with technology. What I learned from the ten religions of Singapore is that traditional practices can comfortably coexist with significant technological change and that what is important is that the moral values of the tradition remain alive and safeguarded online. One can have a busy week working with technology, but it may be more important than ever to have a quiet, protected time and space for connecting with community members and with our spiritual traditions. The conceit of the film title, Technologies of the Soul, after all, is that the ancient practices are themselves too, indeed technologies, that can help us pursue self-development and wellbeing

What advice would you give to religious leaders who are sceptical or reluctant to engage with digital tools, but worry about becoming irrelevant to younger generations?

One of the important findings in social studies of technology is that familiarity with new technologies tends to bring with it a more positive view of them. So, I’d encourage religious leaders to explore the potential of new tools before ruling them out. It may well be that certain technologies overall are harmful, but that is a judgment that requires careful examination, and may take time to arrive at. But religious leaders must lead, and they need to be confident in their traditions and values to be able to tell younger generations what digital tools are doing them harm or promoting bad attributes. After all, technology should simply be a tool that we use to promote our values and live the lives that we believe are in pursuit of the good life. ∞

Technologies of the Soul: Ancient Wisdom in the Smart Nation (2023, Singapore, 60 min) explores how Singapore’s diverse religious communities are adapting age-old rituals to meet the challenges of hyperconnected digital life. Filmed during the pandemic, the documentary reflects on how ancient Asian traditions have reinterpreted rituals, sacrifices, prayers, sabbaticals, and other techniques of the self to carve out spaces outside of time, sustaining inner peace.

AUGUST 2025 | ISSUE 14

SCREENS BETWEEN US