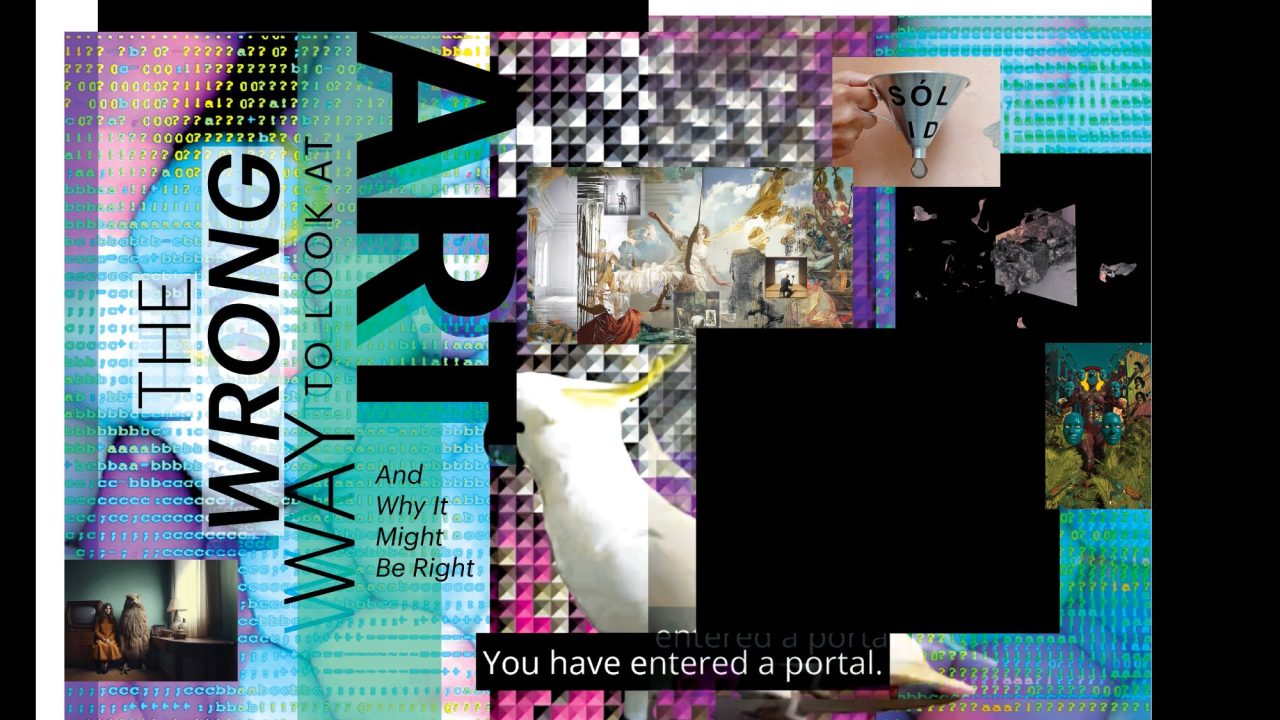

The Wrong Biennale is not a traditional art event. There are no museums, no galleries, and no opening night.

Instead, it lives entirely online.

It began in 2013 as a simple idea: What if anyone could create a digital art exhibition on the internet? No curators selecting who’s in and who’s out. No need for physical space, budgets, or permissions. Just creativity, access, and connection.

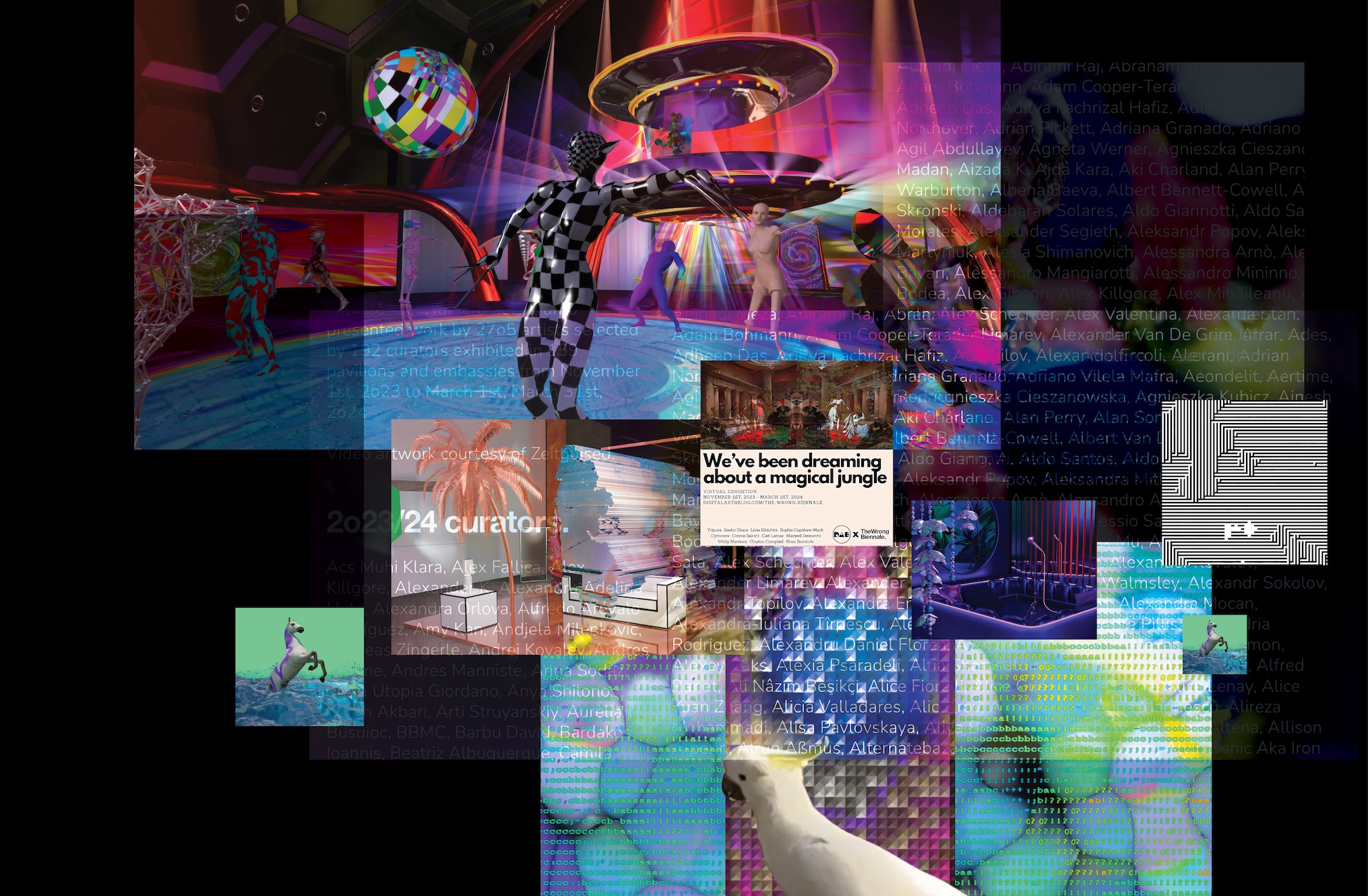

Today, The Wrong Biennale is one of the largest digital art events in the world, with thousands of artists and dozens of online exhibitions called “pavilions,” created by independent curators around the globe. These pavilions are websites, digital environments, or interactive spaces filled with images, videos, texts, and experiments. Some are simple. Some are strange. Many are fun. All are part of a growing global art movement.

In 2013, Spanish new-media artist David Quiles Guilló set out to challenge the stereotyped and outdated ways of exhibiting art, especially in light of the rise of digital culture. He launched The Wrong Biennale with a clear mission: to break free from traditional gallery gatekeeping and make digital art accessible to a global audience.

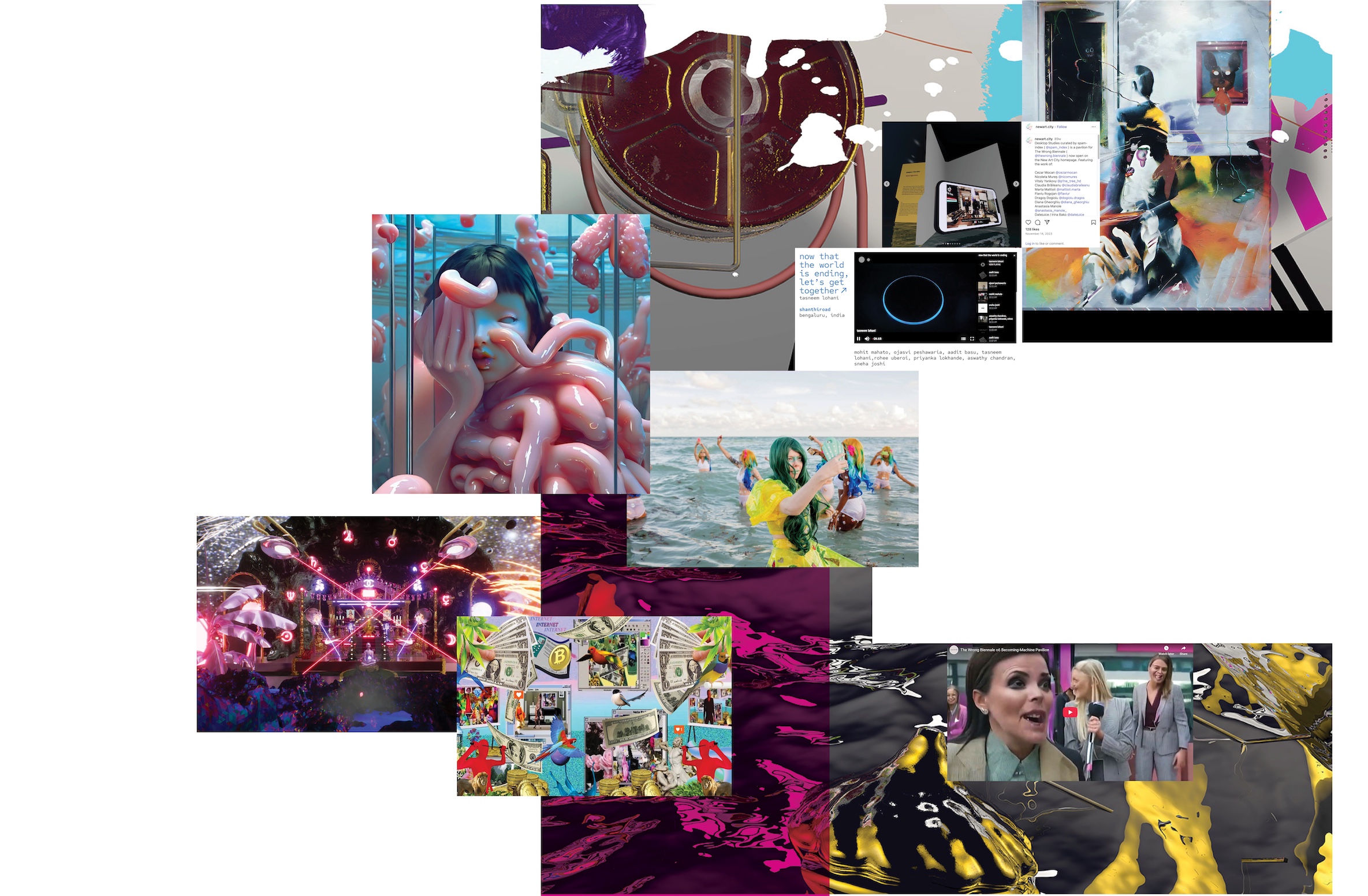

The Wrong Biennale takes place every two years and is built around an open call. Artists and curators submit proposals to host or take part in independent exhibition spaces known as pavilions. These pavilions exist entirely online, most commonly as websites, though some unfold as social media threads, interactive platforms, or experimental web-based environments.

Each pavilion is self-directed. Curators and artists define their own themes, select the works, and determine the format of presentation. Artworks may include videos, animations, sound pieces, AI-generated imagery, short texts, or interactive digital tools. The variety of formats reflects the diversity of artistic approaches and intentions.

There is no fixed route or required entry point. Visitors navigate the Biennale through a central website, where active pavilions are listed. From there, they are free to click, scroll, follow links, or even drift into unexpected corners of the internet. In this way, The Wrong mimics the web itself: decentralised, fragmented, and full of accidental discoveries.

The event is defined by its openness, inclusivity, and experimental spirit. There are no physical venues, no central selection committees, and no overarching curatorial theme. Instead, improvisation, technical failure, and creative detours are welcomed. “Freedom in chaos,” as Quiles Guilló once described it.

Since its inception, The Wrong Biennale has featured over 10,405 artists, working with 843 curators, across 619 online pavilions, making it arguably the largest digital art biennale today. Participants include established names in digital art as well as students, independent creators, and hobbyists exploring the possibilities of online media. Each is given equal space to present their work.

Because of its open and decentralised model, The Wrong often anticipates emerging digital practices before they enter the mainstream. Early editions featured net art (art created specifically for and experienced through the internet), glitch aesthetics (visual styles that embrace digital errors and distortions), and GIF-based works. More recently, the focus has shifted toward AI-generated content, browser-based games, interactive storytelling, and collaborative digital platforms.

The upcoming 7th edition of The Wrong Biennale, scheduled to run from 1 November 2025 to 31 March 2026, reflects this ongoing evolution. It centres on the creative potential of AI in visual, sonic, textual, and audiovisual art, inviting artists to explore generative tools in new and personal ways. Importantly, this edition places emphasis not just on outcomes but on process. Artists are encouraged to document how their works are made — through prompts, sketches, iterations, and decision-making steps — revealing how human creativity interacts with machine systems. The result aims to open a conversation about agency, collaboration, and authorship in a hybrid creative future.

As the artist Nam June Paik foresaw decades ago, the artist of the future would not merely produce static objects, but rather flows of information shaped by technology as the new sculptural materials. The Wrong Biennale doesn’t present finished works to be contemplated in silence; it offers entry points into dynamic, unpredictable environments. It reflects how digital spectatorship works today — fragmented, fast, and networked — but it also shapes it by asking us to pay attention differently.

Digital artwork is, ultimately, not a product but a pathway. It is an informational structure designed to lead to an experience, or rather, to the aesthetic conditions in which experience can occur. In this way, The Wrong is not simply an escape from the mainstream frameworks of contemporary art — biennials, museums, institutions — but a reformatting of them. It mirrors the strategies of informational routing used in those settings, yet transforms them into something more open, unstable, and unfinished.

Like every rupture in art history, The Wrong unsettles older definitions. But that, too, is art’s role: not only to reflect culture, but to question it. And In doing so, it helps us understand why, sometimes, looking at art the wrong way might just be right.

Get a sneak peek into The Wrong Biennale before it goes live again in November.

STELLA LAI

Stella Lai is a designer drawn to misfits, detours, and new ways of seeing.

AUGUST 2025 | ISSUE 14

SCREENS BETWEEN US